The selected material

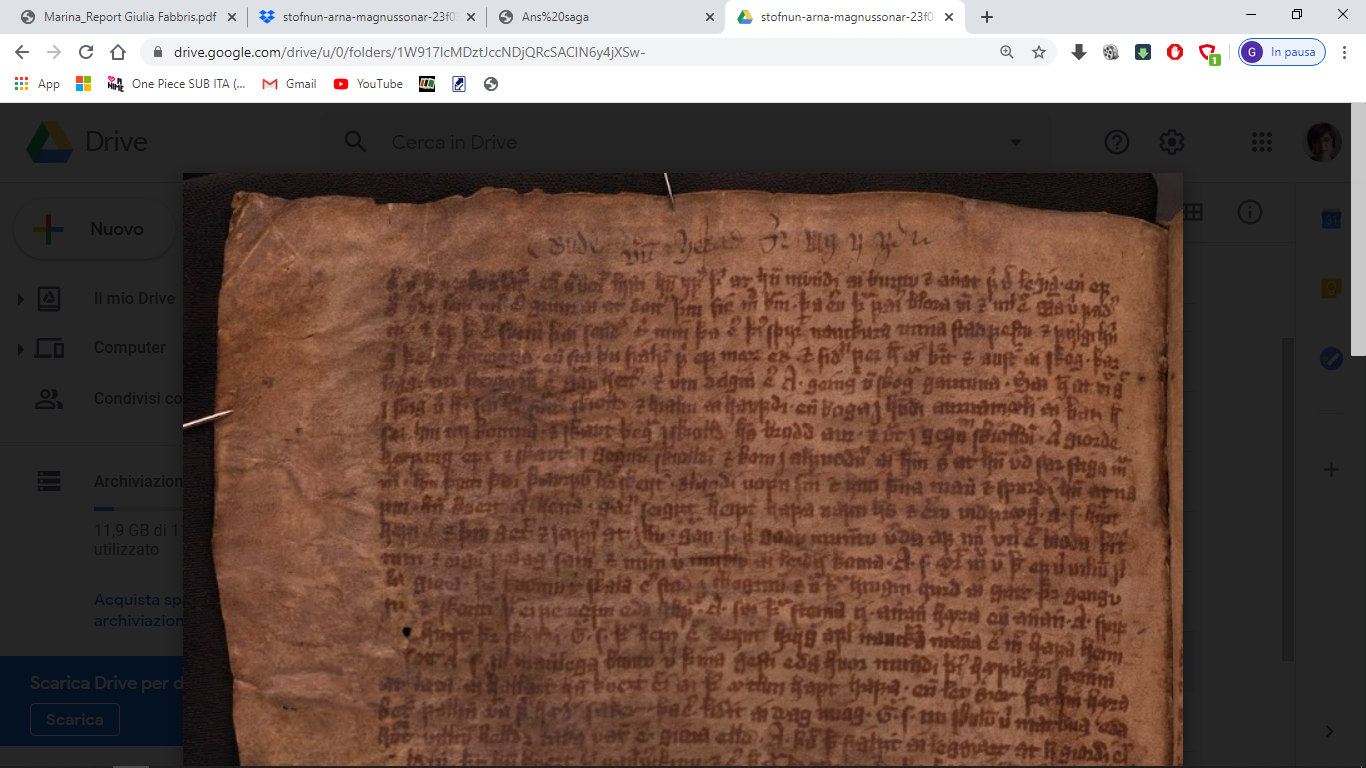

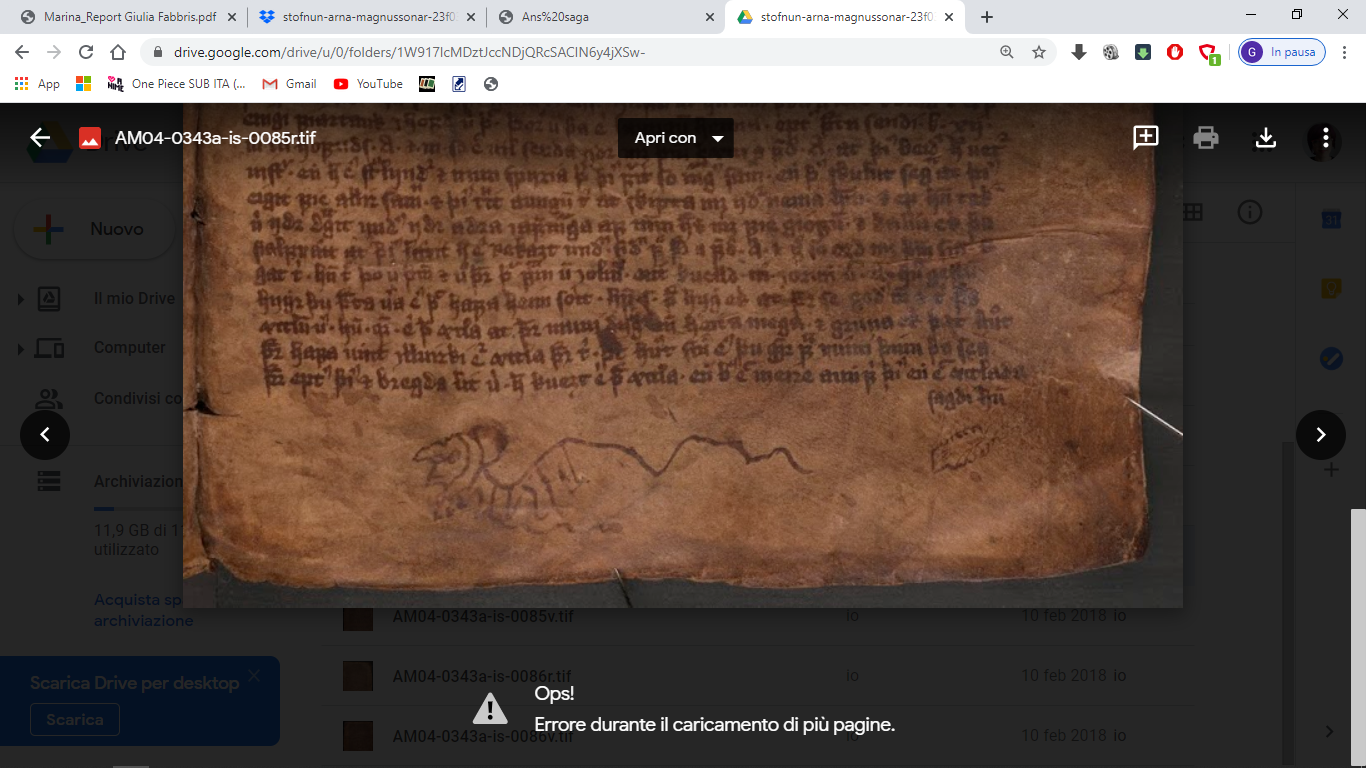

The main actor of this play is, of course, codex AM 343a 4to. Fornaldarsögur began to be written down in the fourteenth century, and our saga belongs to the second half of the fifteenth. This means that more than one century divides the hypothetical first written version and the oldest copy we can actually read. However, it is also true that our manuscript and those that follow in the timeline also stand one century apart. Some of the later versions of this saga are not that different from the fifteenth-century one, so one might infer that the earliest manuscript could not have diverged much.

Bearing in mind that a stemmatic analysis of all the witnesses still needs to appear, I chose AM 343a 4to not only because it is the support that hands down the oldest version of the saga but also because in that manuscript alone Áns Saga has been copied with the other sagas that report the same genealogy, the Hrafnistumannasögur. This shows that some thematic connection among these tales was already detected by the medieval scribes. This manuscript seems to have borne a particular significance already when it was copied under a cultural and social point of view and therefore deserves proper consideration in the editorial process. Moreover, Buzzetti and Rebhein ( ) emphasised the usefulness of digital text editions as being valuable and ready-to-use material for further (critical) editions. My diplomatic-interpretative edition might facilitate the project of a critical edition in the near future.

Folios from 81v to 87r of codex AM 343a 4to were kindly digitised, on my request, by the Arnamagnæan library for the purpose of this work, not being available on the online register of historical manuscripts of the Old Norse tradition.

The manuscript is not perfectly readable in all its parts, so for the worn sections I had to avail myself of other sources. The primary sources I opted for to analyse the manuscript are AM 345 4to and lbs 4547 8vo.

The prototype of the edition

Excluding the most popular sagas, which have attracted much attention and on which

many articles have been written, Áns saga

is interesting because of its hybrid genre. In fact, it has

been attributed to the fornaldarsögur because it fits many requirements of

the category. Nonetheless, it shares many features with the

other most famous outlaw sagas, Gísla saga Súrssonar, Grettis saga

Ásmundarsonar and Harðar saga, which belong to the

Íslendingasögur group. Like these three, Áns saga reports the

protagonist’s ancestry and the family tie is preponderant. Moreover, these four

outlaw sagas all begin with the description of the events that lead up to the

protagonist’s outlawry, while, after the outlawry has been proclaimed, each saga

consists of a series of adventures in which the hero escapes those who try to

capture and kill him

.

Given the importance of this saga, I decided to reproduce it considering the text as actually transmitted in a medieval witness. In fact, as Rafn’s edition is the only version available, the scholarly community study the saga from a non-historical work that bears no connections with the physical support that has brought the text up to our time as well as with the linguistic environment of the scribes. I think it is a great loss, and my edition wants to be a starting point to go beyond this lack. The digital environment can highlight the relations among the different traditions thanks to a set of tools that allow the retrieval of information within the text and can favour further analysis. The following sections will provide the reader with some examples.

I opted for an image-based digital edition, since the possibility to place the digitised manuscript and the edited text(s) side by side gives more and better value to the historical dimension of the saga if compared to a printed edition. These updated methodologies allow one to consider not just the mere linguistic data, but also the physical document that preserves them, which is de facto a witness not only of the text itself, but also of its lively and historical-linguistic dimension.

The diplomatic transcription offers a faithful representation of folios from 81v to

87r of AM 343a 4to, showing all the abbreviations and palaeographic characteristics,

which usually make the interpretation slow and difficult. Of course, the rendition of

the characters was my main concern. I therefore decided to offer also an

interpretative text, where, thanks to the visualization software, the abbreviations

can be expanded and some minor interventions take place in order to facilitate the

comprehension of the heavily abbreviated medieval text. This interpretative level of

representation would provide another missing piece in the edition of the saga, would

make the analysis of the work more complete and the investigation of the saga wider.

I addressed my work to all those scholars and users who seek an assisted

approach to help them read the text. I also hope it might provide an example for

editing other sagas, since I could not find any interactive text of this literary

genre, despite its importance.

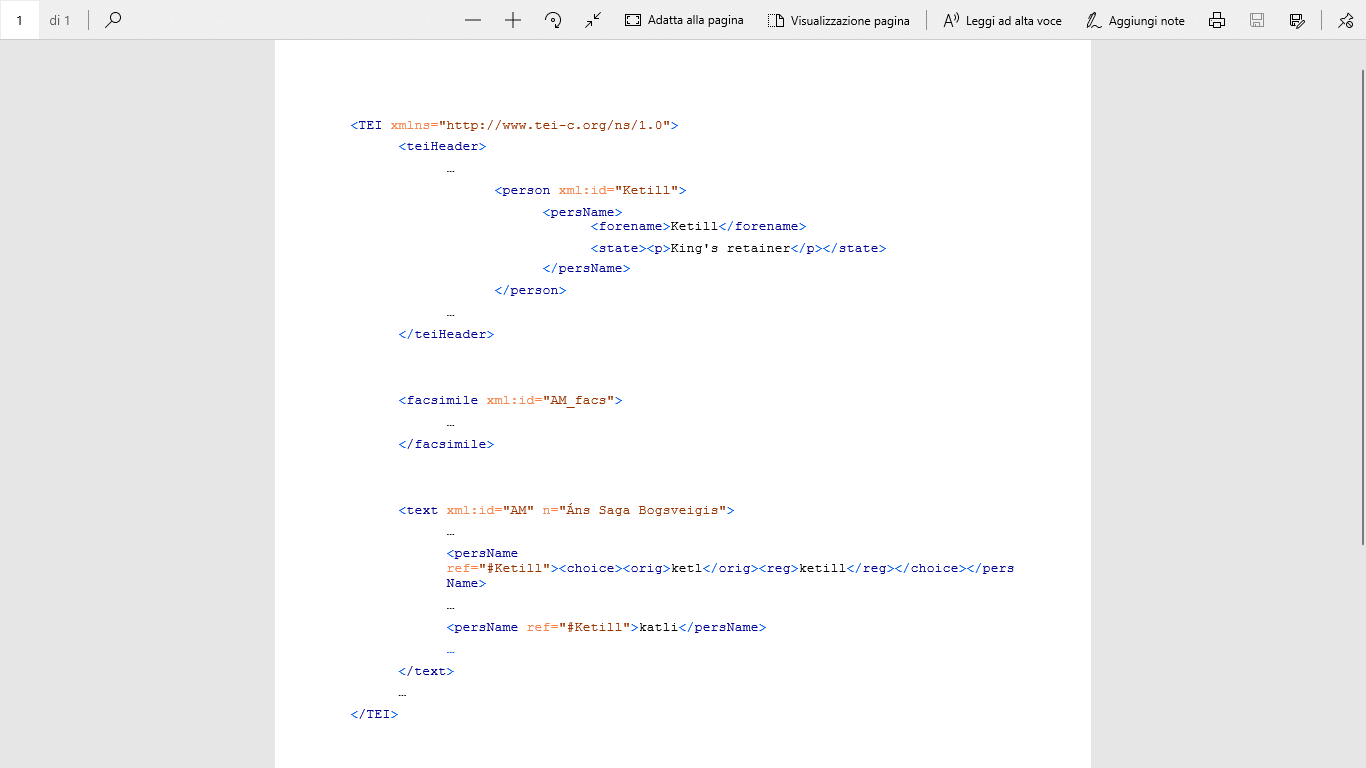

After exploring the digital edition of the Vercelli Book and all of its features, I decided to encode the saga in XML following the TEI-P5 guidelines, which offer a standard for encoding that is strong and flexible at the same time. As a consequence, I decided to use EVT as visualization software. Following the TEI and EVT guidelines, I identified my encoding subset of elements and attributes, selecting the essential or highly recommended elements and personally chosen markup entities according to the scope of my edition. Of course, a full identification of all the entities that I wanted to highlight preceded this phase.

Editorial choices

In this section, I present the features that I decided to analyse and, partially, those that I decided to omit for this level of the edition.

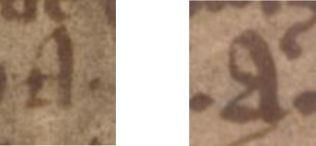

The author of the saga is unknown, as it usually happens within this genre. The writing is clear, neat and quite homogeneous, although I noted some differences that led me to believe that the text was in fact written down by two scribes. This observation has never been made before. Analysing the folios carefully, I noted that some letters differ in shape but what is more evident is the density of writing. Sometimes it is thin and sharp, in other cases it is rather bold and round. Here is an example.

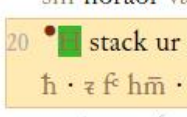

I also observed that the distribution of the abbreviations of the cluster upp supports my hypothesis, since there is coherence between one kind of abbreviation and one hand.

Some capital letters are omitted, and a blank spot is to be found in their place. The first letter found is then capital, so in my interpretative version I added the missing letter in capital as well within the element <supplied>. This element is retrieved only in the interpretative version, so the diplomatic will faithfully have just the second capital letter.

In many folios, the scribes emphasized the first capital letters of some lines, enlarging them and writing them on the left margin, not in line with the rest of the text. Unfortunately, EVT did not offer a visual representation for this case, so I opted for the element <add> that shows the letter in a green background. The item is then described thanks to a <note> that specifies what I have added. It appears as a small dot that can be clicked and a small icon opens with the information of <note>.

Besides capital letters, other elements appear in the margins of some folios. These are writings and drawings, whether on the left, upper or lower margin. Yet, at this stage of the work, they are not edited but only listed in a paragraph within the <physDesc>.

The element <supplied> is used also in the case of ruined vellum, which reports

the reconstructed information thanks to the aforementioned further witnesses. This

element appears in the interpretative level, while in the diplomatic one there is the

element <damage>. In the interpretative visualization with EVT, the word will

be shown in square brackets if the value of the element reason is

illegible

, in angle brackets if the value is omitted

.

Some ligatures were encoded within the element <seg>, even though a deeper encoding might highlight the presence of the two different hands previously identified.

I decided to implement the elements <listPerson> and <listWit>, since I think they are functional and crucial in this type of work. Listing all the people and all the places (see below) of the saga means having all the possible variants of a proper name and of a place linked to a standard one, along with all of the other optional details of the entity in question, according to the desired depth of description and granularity of encoding.

As for the rendition of particular characters, for example specific glyphs, I have used the Unicode Standard and the selection of contributors of the MUFI (Medieval Unicode Font Initiative) recommendations.

Another source I relied on is the Menota (Medieval Nordic Text Archive) handbook, which contains guidelines to represent characters, words and other meaningful units of text consistently and unambiguously in a machine-readable and platform-independent way and is based on the schema defined by the TEI. However, particular characters are regularized as standard Latin letter in my transcription, because they do not have distinct value (uṗſia > uṗsia).

The correspondence between a written character and its phonetic realization is not one-to-one. Different letters can stand for the same sound (e.g. <v> and <u> are used for the same word in different parts of the text, the sound /k/ after <v> is found both as <k> and <q>). I noticed that the irregular use of the voiced plosive <d> and the voiced fricative <ð> seems to further support the idea of the two scribes, since their distributions does not appear to be random. This observation will be subject to a deeper analysis in the future development of my project.

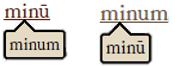

Finally, abbreviations. At the beginning, the elements for abbreviations and

expansions I opted for were, as it might be expected, <abbr> and <expan>.

However, EVT offers a better visual solution with the tags <orig> and

<reg>, so I chose these. In particular, the difference between the <abbr>

and <expan> forms could be seen just changing visualization from the diplomatic

to the interpretative level. On the other hand, with the second option, by placing

the pointer over a word, there appears a little box below it, showing the abbreviated

form if we are in the interpretative edition or the expanded one if we are in the

diplomatic version. Even if my choice is purely a matter of visualization, the TEI

descriptions of the chosen tags perfectly fit my needs: <orig> (original

form) contains a reading which is marked as following the original, rather than

being normalized or corrected

, <reg> (regularization) contains a

reading which has been regularized or normalized in some sense

.

The digital saga

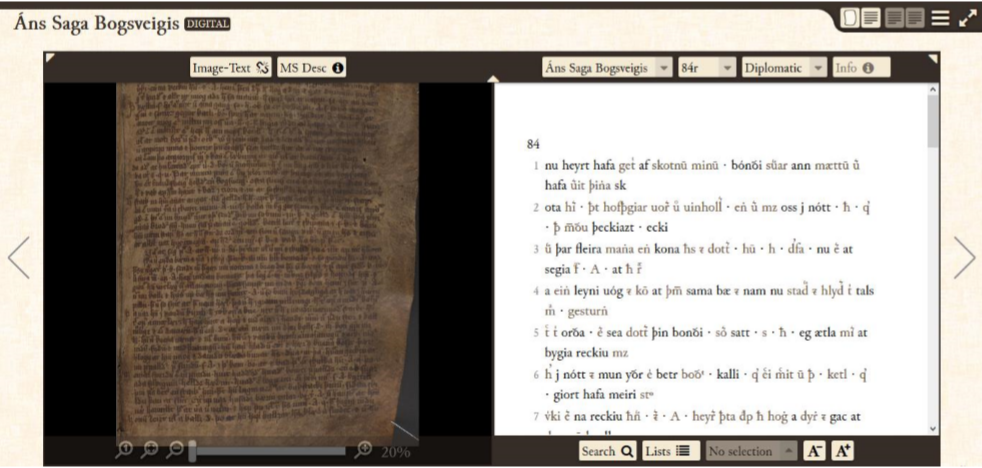

So far, the digital edition prototype offers the possibility to explore one folio (84r) of the manuscript only. Yet, all the folios are encoded at both the diplomatic and interpretative level.

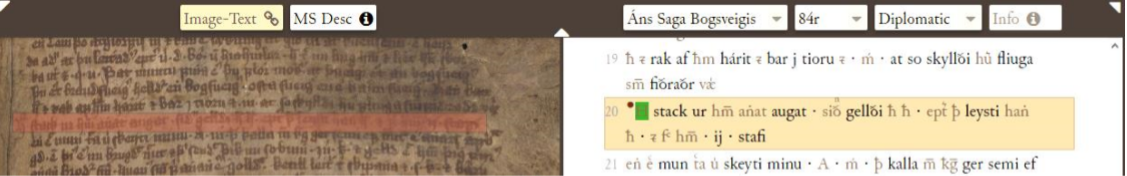

<facsimile> was used to create the link between the image(s) and the text. As stated in the guidelines of EVT, it requires a <surface> for each image and here the editor can also choose to insert the coordinates of each line of the manuscript to enable the linking function that permits to easily connect the respective lines of the facsimile to the edited text.

<text> contains those elements and attributes that interface with the corresponding ones in <surface>, enabling the text-image and line-zone linking. This element is crucial and is one of the most innovative features of this work, since it facilitates the consultation of the text, thus avoiding the loss of time derived from the line search when working simultaneously on the facsimile and one of the edited texts.

The result is a two-page presentation of the different texts. As already mentioned,

the visualization options are three: facsimile and diplomatic edition, facsimile and

interpretative edition or diplomatic and interpretative editions. Above the left

frame, there are the buttons Image-Text

and MS Desc

. The first one

enables the function to link the single lines of the facsimile to the corresponding

ones in the edited text. The other button, quite intuitively, reports the information

gathered in <teiHeader> (location, contents and physical description).

Other information regarding the project can be found in the section in the upper right corner denoted by the hamburger button. On its left, there are the two buttons that allow the folio-text or text-text visualization. On its right, the full screen option.

The facsimile can, of course, be zoomed in. EVT offers other different options for the facsimile. For example, the hotspot function allows to isolate specific areas of the manuscript that can be accompanied by a textual note. More easily, from the configuration file the editor can enable the magnifying lenses and thumbnails.

The search option and the list of personal names help the user in the analysis of the text. Names appear in many graphic variations and, thanks to the implementation of a list, it is possible to group them under a standard form and have all the variants displayed.