Methods and Results

Background

This section offers an intuitive explanation of the bottom mechanism of topic modeling, focusing mainly on the most famous topic model approach, namely the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA).

In the next sections, we will use the following terminology and notation as adopted in .

-

A corpus is a collection of D documents.

-

A vocabulary is the list of all unique words in a corpus ("stop words" excluded).

-

A word (or unigram) is a distinct item from a dictionary (or vocabulary), derived from the training corpus, indexed by 1,...,W. A specific instance or occurrence of a word within a document is called token.

-

A document is a sequence of N words. In natural language processing, a document is usually represented by a bag-of-words (BoW) that is a word-document matrix.

-

A topic is a set of words that occur frequently together. In , a topic is formally defined as a distribution over a fixed vocabulary.

Topic Modeling: Text mining means extracting meaningful insights from written resources through advanced analytical techniques. TMs fall into this very category. In fact, by TMs, we refer to that suite of algorithms used to discover themes that run through words of texts. TMs algorithms are of enormous importance in every field where data is represented by a huge amount of raw text. Indeed, these statistical methods enable us to outline and catalog electronic archives at a scale not feasible by human annotation. In addition, they do not depend upon any prior annotations of the documents to be analyzed. Technically speaking, topic modeling is a machine learning technique. It can be seen as the textual counterpart of the clustering method: while by clustering approach, we attempt to find (unknown) natural groups in items represented by numeric and/or categorical values, with topic model techniques, we try to identify groups of words related to certain unknown subjects. It is precisely for this reason, i.e. the unknown prior knowledge of topic content and presence, that we refer to topic modeling as an unsupervised classification method, like the clustering method is. The model learns that there are repeating patterns of co-occurring terms in a corpus but the learning is not preceded by any training stage (since there are no labeled data to learn). For example, a topic model may derive that the words "knives", "forks", "spoons" all fall under the umbrella of Cutlery

but no label is associated with Cutlery

as a known category.

We underline that, from the grouping text view point, topic modeling is not aiming to find similarities in documents, as text classification does, since topic modeling works at word level. In layman’s terms, a topic model algorithm is able to detect topics in a text by counting words and grouping similar word patterns. The assumption behind these algorithms’ functioning is that each document is composed of a mixture of topics. This, in turn, implies documents consist of a fixed number of topics. Then the goal is trying to find out the proportion of presence each topic has in a given document, where a topic is a mixture of words itself. In most of the TM algorithms, that translates into getting a term-topic matrix, which decomposes topics in terms of their word components, and the document-topic matrix, which describes documents in terms of their topics. The parallelism with the human process for text generation is quite evident. When we want to write a piece of text, first, we decide on the subjects and the importance (i.e. the weight) of each of them for our reasoning; then, we articulate each argument based on a pool of words related to that topic.

There exist several technical methodologies to carry out topic modeling. These can be divided into two categories: TMs performed by vector space models and TMs based on probability models. Some of these models include PachinkoAllocation Model (PAM) , Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF), TextRank , Parallel Latent Dirichlet Allocation (Plda) , to name but a few. However, as TM is not the crux of this work, in this section, we describe a representative algorithm for each category, eventually focusing on Latent Dirichlet Allocation, which is the most common method. The basic vector space model is the Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) : here the assumption is that words and expressions that occur in similar pieces of text will have similar meanings or, rephrased, words with similar meanings appear frequently together (distributional hypothesis). The core of this approach is decomposing via singular value decomposition (SVD) the matrix representing information about documents and terms, in order to obtain a document-topic matrix and a term-topic matrix. In fact, LSA maps terms and documents into a latent semantic space via SVD. On the other hand, probabilistic topic models are those statistical algorithms aiming at discovering the latent semantic structures of the corpus by relying on a document generation process. The idea behind the document generation process, as mentioned above, comes from the human written articles. At heart, probability topic models do simulate the behavior of the human article generating process. For instance, Probabilistic Latent Semantic Analysis (pLSA), to face the same matter of LSA, uses such strategy, that is, a probabilistic approach. Here the goal is thus to find a probabilistic model (instead of the SVD) able to generate data contained in the document-term matrix. Without going into mathematical details, we may affirm that pLSA was certainly a turning point for the probabilistic text modeling sector but did not gain the same success as LDA because it was incomplete, as lacking a probabilistic structure at the level of documents.

LDA: Unlike pLSA, Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) ( ) is the first fully probabilistic model for text clustering, the Bayesian version of pLSA. LDA is a probabilistic generative model, i.e. a machine learning technique that generates an output by considering the prior distribution of some objects. Specifically, LDA draws on Dirichlet priors for the document-topic and word-topic distributions. In plain language, a Dirichlet process is a distribution over distributions. In this section, we will try to understand the model’s mechanism without diving into the math. LDA is built atop the premise that each document can be described by a probabilistic distribution of topics. This allows documents to overlap

each other in terms of content, rather than being separated into discrete groups. Moreover, LDA also assigns a distribution of words to each topic. In other words, the presumption is that a document exhibits multiple topics, usually not many, and each document is generated by a process. Similarly, a topic is generated by a process over a fixed vocabulary. First, each topic is generated, then the documents are produced. This is exactly the generative model for a collection of documents that LDA tries to backtrack from texts, by specifying only the number of topics in advance. LDA attempts to estimate both the mixture of words associated with each topic and the mixture of topics describing each document. It should be noted that LDA, as well as pLSA and LSA, is based on the bag-of-words

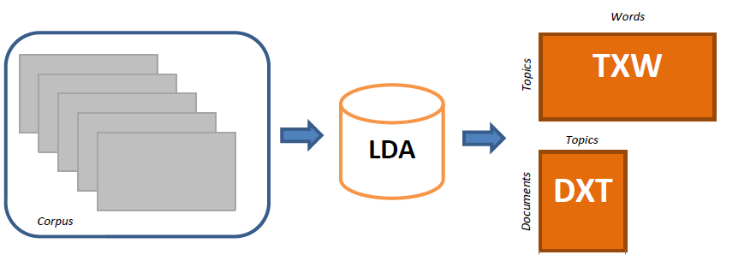

assumption, i.e. within a document the order of words has no importance, meaning words are exchangeable. This exchangeability assumption, which also holds for documents, underpins the whole LDA mechanism. Indeed, following De Finetti’s theorem that states that any set of exchangeable random variables has a representation as a mixture distribution, if exchangeability for documents and words within documents is assumed, a mixture model for both is needed, which is exactly the LDA foundation. Practically speaking, LDA takes as input a document-word matrix (by counting the word presence in each document) and gives as output two matrices: 1) the document-topic matrix containing for each document the topic distribution, and 2) the topic-word matrix providing for each topic the word distribution, as shown in . There are a number of existing implementations of this algorithm. From the computational view point, in this work, we used the LDA variant based on Gibbs sampling (a form of Markov chain Monte Carlo) introduced by Tom Griffiths to prevent correlations between samples during the iteration .

Benchmark Corpus Criteria

In many sciences, benchmark datasets are essential to rigorously compare the performance of different methods, determine the strengths of each technique, and provide recommendations regarding suitable choices of methods for analysis. Yet, there are no official guidelines nor protocols shared by the scientific community concerning the creation of a benchmark dataset, to the best of our knowledge. Nevertheless, unofficially certain essential characteristics exist and are widely acknowledged by the scholarly community. For this reason, to devise a proper and fair corpus, we gathered a set of requirements we know by experience to be critical for a benchmark dataset and translated them into the following criteria:

-

Practicality: it must deal with the machine learning task taken into consideration

-

Difficulty: it must have a sufficient level of difficulty in order not to result trivial

-

Reality: it must be an actual representative of real-world data science problems to be solved with the given tool

-

Diversity: it must have enough features to be interesting

-

Ground truth: it must have clear labels to use as ground-truth

-

Accessibility: it must be open and well documented

-

Quality: it has to be clean but not too clean, otherwise, it would result unrealistic.

-

Size: it should not be too large.

The Corpus

This section provides a detailed description of the corpus from a historical and content viewpoint. Essentially, the following summary is the result of a close reading of the entire corpus carried out by a human being, next used to derive the dataset annotations.

We have put together a corpus of twenty-three works of authors linked in various respects to Édouard Drumont freely accessible in the Gallica the online library of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and Internet Archive: Digital Library of Free & Borrowable Books. Journalist of Catholic orientation, he became intellectual point of reference to French anti-Semites in the 1880s-1890s. Born in 1844 in Paris to a working class family, his father was employed at the Hôtel de Ville, his mother was related to Alexandre Buchon, historian of the crusades and the medieval period, both fervent republicans. Drumont started a journalistic career in 1861 under the patronage of Alfred d’Aunay, putting his name to articles in Moniteur du Batiment and Presse théatrale et musicale. In 1864 he did work for Contemporain. Shortly before the war of 1870 he contributed to the journal Liberté, a collaboration which lasted until 1885. Despite the support of Louis Veuillot, manager of the Catholic newspaper L’univers, he remained a little-known journalist. As a writer he met with little success, as evidenced by two works from 1878 and 1879 respectively: Mon Vieux Paris e Les Fetes nationales à Paris. Our corpus includes a selection of works on the question of Jews in France during the second half of the 1800s: half of these texts, marked as "friends of Drumont", were written by authors of antisemitic orientation close to Drumont, the other half, labelled as "enemies of Drumont", includes volumes of opponents of anti-Semitism. To this work a reference text to frame Drumontian thinking has been added.

In 1886 a hefty work in two volumes entitled La France juive. Essai d’histoire contemporaine ( ), a true and proper manifesto of anti-Semitism was released to the press. Although the subtitle of the work suggests an essay of contemporary history, on reading it is as if one is before an enormous cauldron of commonplace assumptions on Jews which includes Catholic, social, racial, economic, and conspiratorial anti-Semitism. The author of the work, which sold 65000 copies in the year of its publication, was Édouard Drumont. The success of his work - between 1886 and 1912 it was reprinted 200 times - depended on the waves it made in the intellectual milieu of the era and its impact on the popular masses attracted by the synthesis of anti-Semitism of the right, of a church worried about laicization, and anti-Semitism of the left, anti-capitalist and laical. In 1889 Drumont founded along with Jacques de Biez, Albert Millot and the Marquis de Morès la Ligue Antisémitique de France to which they gave the motto France to the French

. In 1897 at the initiative of Jules Guérin he set up la Ligue Antisémitique Française with the intent of reviving the moribund Ligue Antisémitique de France . The members of Ligue came from the popular classes and distinguished themselves for their violent methods. Drumont was honorary president. Within our corpus we have included the collective volume Rothschild, Ravachol & Cie (1892) by the organization "Morès et sesamis" founded in 1891 by the Marquis de Morès which describes the influence exercised by Jews on French society through an enquiry into the strategy put in place to take control of the managing class and the social and economic structures of the country. The authors underline the role played by freemasonry, by the war conducted against the catholic world and unions, to the alliance with the English up to the condemnation of the Franco-Russian alliance. As a result "Morès et ses amis" examines the role of the Bank of France revealing how it was entrusted to Rothschild, considered to have preferential access to state funds. The agents "knowing and unknowing" of Rothschild are "the freemasons, the press, the markets, the red spectrum" (p. 6). Therefore it was necessary to intervene politically so that the Jews, classed as foreigners, lost a privilege that instead belonged to the French people and which was used to sustain agriculture, commerce, and industry. From an analysis of the network surrounding the collaborators we can deduce that Drumont assiduously cultivated relations with people linked to the, such as the literary salon run by Alphonse Daudet, and press, in particular his immediate colleagues at the journal La Libre Parole, founded by him in 1892, that was first to report the arrest of Dreyfus on 29th October 1894. One of the texts examined is by Léon Daudet, son of Alphonse: Souvenirs des milieux littéraires, politiques et médicaux (1920). In these memoirs Daudet outlines how it was initially the literati and journalists who made known the writings of Drumont. People who would then go on to espouse the anti-Dreyfusard cause, were already actively engaged in the diffusion of anti-Semitic ideas well before the Dreyfus case exploded. Somewhat different are the volumes of the corpus written in the journal La Libre Parole

. We can mention Caroline Rémy de Guebhard known as Séverine ( ), socialist journalist and feminist who wrote in La Libre Parole in the years 1894-1896, author of Vers la lumière...impressions vécues: affaire Dreyfus (1900), Jean de Ligneau, pseudonym of François Bournand, special secretary to Drumont and coordinator of the news section of La Libre Parole

, author of Juifs et antisémites en Europe (1891), the anti-Semitic adventurer and editor of La Libre Parole

, the Marquis de Morès ( ) or again Isaac Blümchen, psuedonym of Urbain Gohier, a rather complex, and in many ways contradictory figure ( ). Dreyfusard, friend of Émile Zola, anti-Semite, socialist e anti-militarist Gohier collaborated with La Libre Parole

in 1908. Victor Célestin Méric, pseudonym of Henri Coudon, defended him from those who attacked him for his anti-Semitic position in an article published in Les Hommes du Jour

, 6 March 1909: Without doubt, whether at Libre Parole or at Intransigeant, on the right or the left, Gohier continued tirelessly the same work and found himself, forever poor, forever indifferent to material gain, on the same side of the barricade

. His collaboration with Drumont made Gohier the subject of hostility of many colleagues, among them the anarchist Jean Grave, who accused him of being an armchair revolutionary and who in his novel Les Malfaiteurs (1903) found it amusing to portray him as Roguier to reveal his bad faith. A good part of the text of the corpus is about l’Affaire Dreyfus. Of particular note in the section of the corpus on "enemies of Drumont" are two works by Émile Zola, credited with the celebrated editorial J’accuse published on13 January 1898 in the journal L’Aurore in which, addressing the then President of the Republic Félix Faure, the writer denounces the irregularities that occurred in the trial to the detriment of Dreyfus. In the corpus we have Lettre à la jeunesse: l’affaire Dreyfus (1897) and Lettre à la France: l’affaire Dreyfus (1898). The first is an open letter to French youth invited by Zola to rebel against what he viewed as a social injustice: the trial and the conviction of Dreyfus, was more correctly a "judicial error" (p.6). Zola, turning to his interlocutors exhorts them not to squander what has been achieved to date by the preceding generation and instead carry forward the social and political gains achieved. In Lettre à la France: l’affaire Dreyfus (1898) Zola calls upon the entire nation, France, to pay attention to the danger contained in anti-Semitism. He emphasized the role of newspapers, in particular L’Écho de Paris and Le Petit Journal, in having influenced public opinion by publishing false news and generating fear and intolerance. Zola denounced the silence and more in general the lack of interest shown by parliament with respect to the intrigue. The text is constructed around the crucial importance of truth, which he stressed several times: "I will dare to say everything, because I have always had one passion in my life, the truth" (p.4). L’affaire Dreyfus is furthermore object of discussion by authors close to Drumont, such as Séverine, who in Vers la lumière... impressions vécues: affaire Dreyfus proposed as a court reporter, to report the facts, to throw light on the protagonists and on their conduct seeking to depict the climate created in that period characterized by disorder both in and outside the halls of the tribunal. Séverine accused certain sections of the press of having diffused false and distorted information. In the course of the narration it is possible to discern an evolution of the position of the author on the guilt of Dreyfus: initially firmly convinced of his guilt, she gradually evinces a certain perplexity about the trial, the irregularities and errors committed at the judicial level and concluded with an affirmation of the innocence of Dreyfus. Even so Séverine did not nurture any special empathy for Dreyfus and expressed anti-Semitic sentiments, in particular when she referred to the wife of Dreyfus (“She is not of my religion, and not of my race [... ] And if I don’t like the colour of their skin anymore than I don’t like, in general, the Jewish soul, this was not a reason to approve of their torture!" (p. 68). In the end she fell into the camp of those who fought for the liberation of Dreyfus in the name of the struggle for "Truth") (p. 461).

In the corpus we have included a series of works that from two points of view diametrically opposed interpret the role of the Jew in society. Among the authors that dominate the corpus is Bernard Lazare, poet-anarchist, a convinced Dreyfusard, who in the volume L’antisémitisme: son histoire et ses causes (1894) set out to reconstruct the origins and the deeper causes and long duration of anti-Semitism. Lazare proposed a historical-sociological study that was impartial and that made a lie of all the voices that depicted him as anti-Semitic one moment, philo-Semitic the next. He analyzed the social, economic, and political context within which the transformations and changes in anti-Semitism had matured, and at the same time enquired into the role played by Jews in the intellectual, economic, social, and political fields. According to Lazare, to feed the anti-Semitic sentiment of many were elements innate to the Israelites, that is, congenital traits, such as asociality, resistance to integration because of the unity of morality and politics in Jewish religion. Beside these endogenous causes, the author identifies exogenous causes strongly linked to the historical epoch and particular context. According to Lazare, modern anti-Semitism originates from hate for the stranger and as a consequence, for Jews, who were viewed as a foreign minority. However, in his opinion, anti-Semitism was destined to disappear thanks to the progressive assimilation of Jews in contemporary society and to the development of the ideals of socialist internationalism (p. 408-409). On the other hand we have included in the corpus authors who are strongly anti-Semitic, such as forementioned Gohier, who in À nous la France (1913) claimed, writing in the first person singular and plural, and making extensive use of irony, all the weaknesses revealed how much France and the French were under the yoke of Jews, whose ultimate objective was the conquest and control of the world. Therefore he eulogizes ironically the conduct of several French ministries and politicians that served the Jews, who in virtue of French naturalization, had succeeded in climbing the social ladder and obtaining prominent positions. Of the same tenor is the volume Droit de la race supérieure (1914) in which Gohier describes the right of the superior race, the Jew, to dominate that which is inferior, the French, as a law of nature. To support this thesis he mentions the dominance of Jews in education, politics, the judiciary, the press, and freemasonry. Gohier dwells on the situation of the colonies, revealing how the Arabs, despite having served France, had never obtained, in contrast to Jews, citizenship. Finally a conspicuous part of the corpus deals with the question of anti-Semitism in Algeria. Anti-Semitism in Algeria was also a relevant aspect of Drumont’s personal network. In 1892 la Ligue anti-juive d’Algers was founded at the initiative of Émile Morinaud and Max Régis. Morinaud was socialist republican deputy and member of the Parti Radicale Antijuif, a leading light in the Algerian anti-Semitic movement. Régis was a naturalized Frenchman and distinguished himself in his university days for his fervour as a political agitator. He refounded in Algeria a "Comité Central Républicaind’UnionAntijuive" in 1898 drawing inspiration from Ligue Antijuive established in 1892 by Fernand Grégoire ( ). In January 1898, a crowd led by Régis torched central Algiers for five days, killing two people and destroying the synagogue and several homes ( ). Max Régis had a central role in the candidacy and election of Drumont in Algeria. It was at the suggestion of Régis that Drumont put himself forward for election in Algeria in May 1898 and was elected deputy as part of the anti-Semite group ( ).

One of the texts of the corpus is Les mémoires du prisonnier Max Régis (1899) consisting of the memoire written in prison by Max Régis collected by his friend Louis Gardais and published in “Mustapha imprimerie spéciale de L’Antijuif”. In this account Régis talks of his incarceration for four months and rails against the French government, the local administration, and in particular the prefect of Algiers Charles Lutaud. The government in Paris was accused of showing no consideration for the people of Algeria and at the same time of being manipulated by Jews. Régis did not neglect to outline how popular he was in Algeria reproducing extracts of the letters that he received from supporters, friends and political figures such as Drumont but also from his mother who urged him to terminate his "struggle" as "the Jews will always have the power to impose the governor they wish, and it won’t be our revolt, however beautiful or legitimate it might be, that will impede this"(p. 6). From another point of view, opposed to that of Drumont, is the volume L’antisémitisme algérien (1899) that reproduces a speech from the chamber of deputies on the 19 and 24 May 1899 by Gustave Rouanet ( ), socialist deputy for la Seine, addressed to Algerian anti-Semitic deputies. The intention of Rouanet was that of demonstrating the inconsistency of the anti-Semitic discourse, confuting the arguments, in particular those that outlined the financial and economic wealth of Jews. In his view social criminality did not originate from the supposed wealth of Jews, but from the harm generated by capitalism. Rouanet outlined how before the Crémieux decree of 1870 bestowing French citizenship on Algerian Jews, they had done their military duty fighting beside the French. The naturalization of the Jews in Algeria brought about a hardening of anti-Semitism, which until then was not widespread, and helped aggravate an already tense situation due to the presence of Italians and Maltese who cultivated an "ancient hatred of Jews" (p.33) and that with their traditions, habits, and mentality had undermined the French spirit distancing Algeria from France.

We remind the reader that the corpus can be easily built by downloading from Gallica and Internet Archive: Digital Library of Free & Borrowable Books the document raw files, in txt format. Alternative, all files are also available at the following Link.

contains some information about the size of each documents. In particular, we can find the number of characters and words in the original texts, the number of words obtained after tokenization and stop word removal, the number of unique tokens in each literary work and the percentage of each documents based on the total number of characters in the original versions. This last column of the table deserves some remarks. Souvenirs des milieux littéraires, politiques artistiques et médicaux de 1880 à 1905 occupies 21.23% of our corpus because it deals with a central theme, namely the relationships matured within the intellectual salons in the period under discussion. These memoirs, by Léon Daudet, son of Alphonse (main entertainer of the Parisian literary circles of the time as well as a Drumont’s friend) allow us to reconstruct the overall picture of the network of acquaintances within the anti-Semitic milieu as well as the dynamics that involved the opposing sides, that of the dreyfusards and the antidreyfusards. Still substantial (15.05%) is La France juive, Drumont two-volume work that represents the sum of anti-Semitic arguments, in which the main topic of our study dominates: anti-Semitism. Although they do not have a similarly large percentage (respectively 1.65% and 0.8%), the two texts by UrbainGohier - A nous la France and Le droit de la race supérieure - focus on the theme of the influence of Jews in French society according to a pattern of interpretation of conspiracy theorists. The topic relating to the Affaire Dreyfus is present in some works, some of which are relatively short since they are letters (Lettre à la jeunesse and Lettre à la France by Zola) in which, nevertheless, the subject is examined in-depth and where we can identify homogeneous sub-themes, such as the concept of law, justice, truth. Other documents, written by non-anti-Semitic authors, with a percentage between 0.42% (Antisémitisme et révolution by Lazare) and 9.23% (L’antisémitisme: son histoire et ses causes by Lazare), are uniform in terms of topics: the Dreyfus Affaire and the origins of anti-Semitism. Those texts addressing the issue of anti-Semitism in Algeria and the status of Jews in that country are also homogeneous (they represent 26% of our corpus). Four of them are argumentative books, with a percentage between 4.78% and 7.46%, one book is a biographical account of Max Régis (0.43%), a leading exponent of anti-Semitism in Algeria, the other one is a condemnation speech of the anti-Semitic movement in Algeria pronounced by Gustave Rouanet.

Based on human interpretation (close reading), it was possible to identify the topics, divided into macro-topics and sub-topics, present in the collection of documents. It should be stressed that these are the themes detected by a human expert blindly, that is, without thinking in terms of ground truth for the machine. The addition of the related keywords was performed as a subsequent stage. It was derived from a set of words, a dictionary. This set of words was retrieved by selecting the most relevant terms by topic obtained through the implementation of the LDA method over our corpus, as described in 3.4 but fixing the number of topics parameter to k = 15, to have a larger basin of terms. Specifically, in the macro topics and related subtopics are reported along with their keywords while is an outline of the documents in the corpus, annotated with topic information: title (original and translated), author(s) name, document typology, position of the author(s) with respect to Drumont where F stands for Drumont’s friend while E indicates an opponent, number of topics present in the work and content of these topics. Since the corpus is completely written in French we provided keywords both in English and French, to help the user in understanding the content.

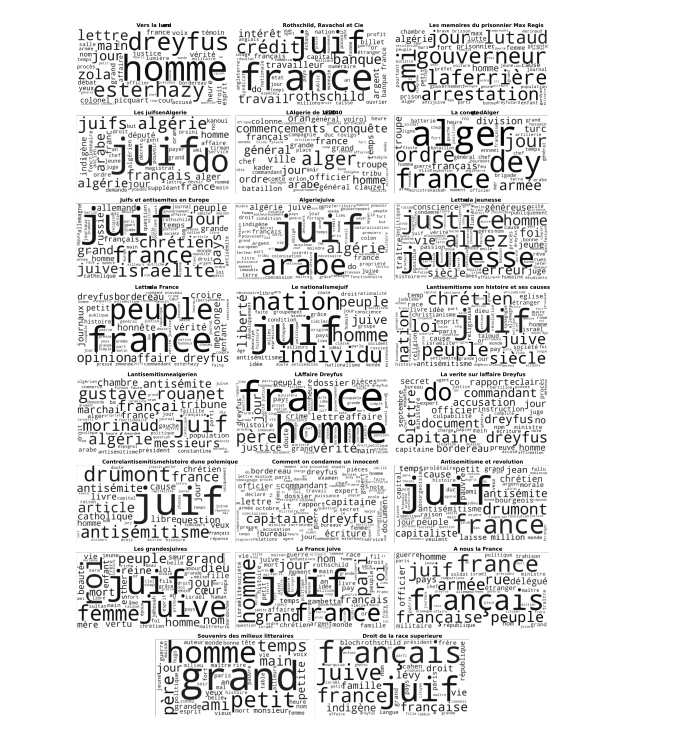

It is of interest to compare words we expect in documents based on and , and most common words contained in them, by frequency. To show word frequency, we used a well-known graphical representation, i.e. word clouds, as depicted in . Here, we can immediately notice as the word juif is the most frequent, along with france, homme and peuple. Even if they are explanatory for an initial investigation, in terms of topic modeling viewpoint they are too general. Also from the content viewpoint they are vague. For instance, in Souvenirs des milieux litteraires, politiques, artistiques et medicaux de 1880 à 1908 and Les grandes juives de l'histoire the wordclouds highlight words such as "man", "great", "father", "Jewish woman" which are not significant at all for the actual topic, i.e. the intellectual circles in France at the time. Based on the close reading we expected to find words such as Daudet

, Hugo

, literature

, and Paris

. Another example of fuzzy terms concerns the two wordclouds of Urbain Gohier's works, A nous la France and Droit de la race supérieure. In this case there should be words related to the theme of Jewish conspiracy and Jewish influence in French society, such as Rothshild

, money

, and bank

, instead we find army

, France

, and Jew

, which unarguably common terms. On the other hand, Les mémoires du prisonnier Max Régis wordcloud shows adequate results: in particular, it emphasizes the names of Charles Lutaud, prefect of Algiers in 1898, and Julien Édouard Laferrière, governor general of Algeria from 1898 to 1900 and responsible for revoking Régis' mandate as mayor of Algiers.

Results

In this section we will discuss how the created corpus meets the benchmark criteria we set and we will see a basic utilization of the corpus as benchmark dataset for topic modeling. It should be pointed out that the corpus may be employed in several other NLP research cases since each document is annotated and the most prominent words are contextually clustered.

How does the Corpus Meet Benchmarking Criteria?We attempted to fulfill all set requirements. In the following, we report how we tackled criteria.

-

Practicality → The dataset deals with topic modeling task (it is a collection of documents of which we are interested in finding out topics).

-

Difficulty → The number of topics and subtopics makes the task quite challenging.

-

Reality → The corpus is an actual example of a collection of documents to be studied by historians.

-

Diversity → There are different types of documents (books, letters, etc.) and themes. Novels have not been considered for the construction of the corpus intentionally, as they are not suitable for the topic modeling tasks.

-

Ground truth → There are labels both at document and word level.

-

Accessibility → The dataset is freely accessible.

-

Quality → All documents are from official online repositories with policies about OCR level.

-

Size→ The number of documents is sizeable but at the same time allows to perform LDA analysis quickly (a few minutes via Google Colab Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU 2.20GHz, RAM 12 GN Disk 108 GB).

LDA Experiment We carried out the LDA experiment in Python, by adopting standard NLP libraries, such as gensim and nltk. To preprocess the text we tokenized the text documents (by splitting the entire corpus into smaller units, i.e. individual terms) and removed stop words. Stop words are the set of commonly used words in any language. The list of French stop words is provided at the following Link. We did not perform any stemming process. Tokens have not been filtered out by their frequency (we kept tokens which are contained in i) at least 1 document ii) in no more than 1 expressed as fraction of total corpus size, that is, the whole corpus). We performed the LDA Mallet Model, by Andrew McCallum, McCallum ( ) in Python through the gensim wrapper gensim.models.wrappers.LdaMallet. We fixed the number of topics to be 5 (as many as the macro topics) and the number of training iterations equal to 200 (default value is 50).

In results of LDA application with k = 5 are reported. Each column represents a topic and contains the words the machine detected. Words are in descending order, that is, the most important words are at the beginning of the list. Then, to exploit our annotations, we employed the Jaccard similarity (Js) to assess the quality of the predicted topics. Js is a measure commonly adopted to compute the similarity between two objects, such as two text documents. Jaccard similarity can be used to find the similarity two sets and it is defined as

where A and B are the two sets, ∩ and ∪ denote intersection and union, respectively. The Jaccard similarity index (sometimes called the Jaccard similarity coefficient), ranges from 0 to 1. The higher the percentage, the more similar the two populations. In other words, we count the number of members which are shared between both sets and divide by the total number of members in both sets. In in the bottom row of we reported the Js between each topic found via LDA and the actual topics (in bold the highest value). Without studying the word lists but only these values, we can affirm that by using k = 5 as parameter we did not obtain a perfect clustering. Indeed, if LDA had identified all the themes correctly, we would have just one sharp Js match for each predicted topic. Nevertheless, we can keep appraising LDA results by studying these predicted labels. For instance, by comparing and , we can say that 16 out of 23 topic assignments are correct.

Notably, the topic about the anti-Semitism (topic #1) appears to be the most important in both works written by anti-Semitic authors, including La France juive (0.3338), and by strong opponents of anti-Semitism [Juifs et antisémites en Europe (0. 4116), Le nationalisme juif (0.5443), L'antisémitisme son histoire et ses causes (0.707), L'antisémitisme algérien (0.3374), Antisémitisme et révolution (0.4412)]. The close reading confirms the results of the distant reading as concerns works focusing on anti-Semitism and its history. The close reading also confirms the assignment of topic #1 and #2 (about anti-Semitism and Algeria respectively) to the volume L'antisémitisme algérien by Gustave Rouanet.

Topic #2 regards the French conquest of Algeria. Indeed, we can find it in both L’Algérie de 1830 a 1840 (0.7878) and La conquête d'Alger (0.7821). Here again, we can observe a correspondence between the close reading and the distant reading.

Topic #3, related to the discussion about the Dreyfus Affair, is correctly prevalent in those works dealing with the French army officer story. Both distant and close reading give us this result without equivocation: Vers la lumière (0.6027), Lettre à la jeunesse (0.7289), Lettre à la France (0.8321), L'Affaire Dreyfus (0.7409), La verité sur l'affaire Dreyfus (0.7432), Comment on condamne un innocent (0.7024). It is surprising, but only apparently, that Les memoires du prisonnier Max Régis is among works where topic #3 prevails, followed at a short distance by topic #4 concerning Algeria (0.2238). The close reading suggests that the text focuses on Algeria. However, although the Dreyfus affair is not mentioned in these memoirs, we can observe a vocabulary in which, coherently with the themes dealt with by topic #3, criticism of the government and of the alleged injustices suffered by the prisoner Régis emerges. In these memoirs, for example, there is a letter signed by Régis' mother in which she underlines her son's combative attitudes against the injustices he had to undergo by the French government. It means that Régis's condition can be compared, from the lexical terms viewpoint, to the Dreyfus one.

Topic #4, the one without a clear label, unexpectedly emerges in those documents concerning the presence of Jews in Algeria, such as Les juifs en Algérie (0.6093), L'Algérie juive (0.753). It is also the main topic for the work about the symbol par excellence of Jewish conspiracy, namely the Rothschild family, Rothschild and Ravachol et Cie (0.5148) and for Droit de la race supérieure (0.3569). While for those texts definitively about Algeria the assignment is clearly misplaced, actually for Gohier work it is not, from a historical expert perspective, as the volume treats all the anti-Semites arguments. Instead, A nous la France does not have a prominent topic as expected since it does discuss a larger set of issues. Finally, we find the correspondence between distant reading and close reading by looking at topic #5 assignments. This topic focuses on the relations between intellectuals and Jews. It is the most prevalent in Souvenirs des milieux littéraires, politiques artistiques et médicaux de 1880 à 1905 and in Les grandes juives. The former depicts the intellectual milieu of the second half of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century; the latter provides the new generations of French Jewish women some fundamental lessons drawn from the stories of the great Jewish women, highlighting their virtues and intellectual gifts. In both cases we can affirm that there was a correct assignment.